What’s the difference between accessible, inclusive, and ethical design? It’s easy to use the three terms interchangeably. But they’re not the same. And while some designers may disagree on the details, it’s important to understand the broad distinctions.

Accessible Design

Accessible design is the creation of products or interfaces so that people with disabilities can use them. One common example of accessibility is a ramp, put beside stairs. The stairs are the most direct way up, but the ramp is more accessible for people in wheelchairs or on crutches.

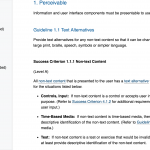

The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) outline how to create digital properties that are accessible for people with visual, auditory, and mobility disabilities. The current WCAG guidelines are WCAG 2.1.

Inclusive Design

Inclusive design goes a step beyond accessible design. Where accessibility accounts for people with disabilities, inclusive design is for everyone.

One common example is a ramp into a swimming pool. The ramp is easier for people who can’t take the stairs, but it’s also helpful for people who:

- like to ease into the water,

- are carrying a child,

- or are afraid of the water.

In another example, an accessible design might be all black and white, with a very large font. That would have a high contrast, which is beneficial to people with poor vision. But it’s not an attractive look. An inclusive design is beneficial to everyone.

Microsoft’s Inclusive Design site created a Persona Spectrum to show the many types of “disabilities” we all encounter, which make inclusive design so important.

Some authors will define inclusive design as the method for reaching universal design. Others argue that universal design is one-fits-all, where inclusive is one-fits-one. Here is where we stumble into ethical design.

Ethical Design

Ethical design is the most complex of the three. Let’s start with an overly simplistic view.

- Accessible design has the “simple” choice. Just make the design better for people with disabilities.

- Inclusive design asks the designer to make a decision that benefits people with disabilities as well as other people.

- Ethical design requires the designer to consider who else may be impacted.

Slate provides an example of a soap dispenser where the sensor can’t recognize dark-skinned hands. While the soap dispenser may be a solution for accessibility and the designers may have thought it was inclusive (since you don’t need two hands to use it, and it cuts back on germs), it wasn’t. It is only usable by caucasians, meaning it’s not inclusive. And to put it out into the world is unethical.

Ethical design is complex because it’s open-ended. There is no single checklist for ethical design. There is no WCAG for ethics. Ethical design requires an understanding of the people who use the product. That means things like:

- diversity within the product team

- personas, including edge cases (remember, many accessibility issues are missed because they are not covered by the persona accounting for 80% of the audience)

- understanding the affects of culture and socio-economics on personas

- cost/benefit analyses – because there will be difficult decisions

In other words, where you may check for accessibility, and design for inclusive solutions, you need to plan for ethical solutions. It takes time and effort, but it’s the only way to design for real people, and real life.