A clinician I work with recently synopsized our work writing clinical content brilliantly: “If the content isn’t accurate, it’s harmful. But if it’s not usable content, who cares?”

This is at the heart of content strategy for healthcare. “Acute Myocardial Infarcions may lead to impairment in diastolic and systolic function” is clinically accurate, but hard to understand. “Eating fatty foods will give you a heart attack” is easy to read, but not accurate. The best language will consider both clinical accuracy and readability.

Making clinical content both accurate and usable is a widespread problem. Most recently, we’re seeing it in the American Medical Association. The AMA’s new publication, “Advancing Health Equity: A Guide to Language, Narrative and Concepts”, tells providers to use more accurate and equity-focused words. But if the equity-focused words aren’t understandable, then who cares?

The AMA’s new guidelines for clinical (and equitable) accuracy

In one example showcased in The Atlantic, CDC Director Rochelle Walensky said “We know that vaccination helps to decrease community transmission and protect those who are most vulnerable.” Under the new guidelines, she might say “We know that vaccination helps to decrease community transmission and protect those who are most oppressed.”

The key word that The Atlantic pulled out is “vulnerable.” Since people are not on their own vulnerable (but rather, made vulnerable through oppression), it is more accurate to use the new language. But when it comes to medical language, the two aren’t the same. Vulnerability can come from oppression – but it can also come from genetics or age or illness.

Context matters

True content strategy is about more than the words. On top of thinking about accuracy and readability, a health content strategist needs to consider if the content is appropriate for where reader’s physical and emotional context. Walensky was trying to explain why vaccines are good. A word like “vulnerable” helps people to think about protection, and vaccines give protection.

Context is also relevant when we think about where and why people talk to their providers. As Matthew Yglesias says in Slow Boring, “

…[Alex] Tabarrok‘s critique is that “politicizing medicine is dangerous,” while [Conor] Friedersdorf similarly says, “It’s already hard enough to get my conservative grandfather to heed his doctors about how best to care for a bad back worn down from decades in construction” and worries about the impact of medical professionals coming across as alienating leftists.

Matthew Yglesias, Slow Boring

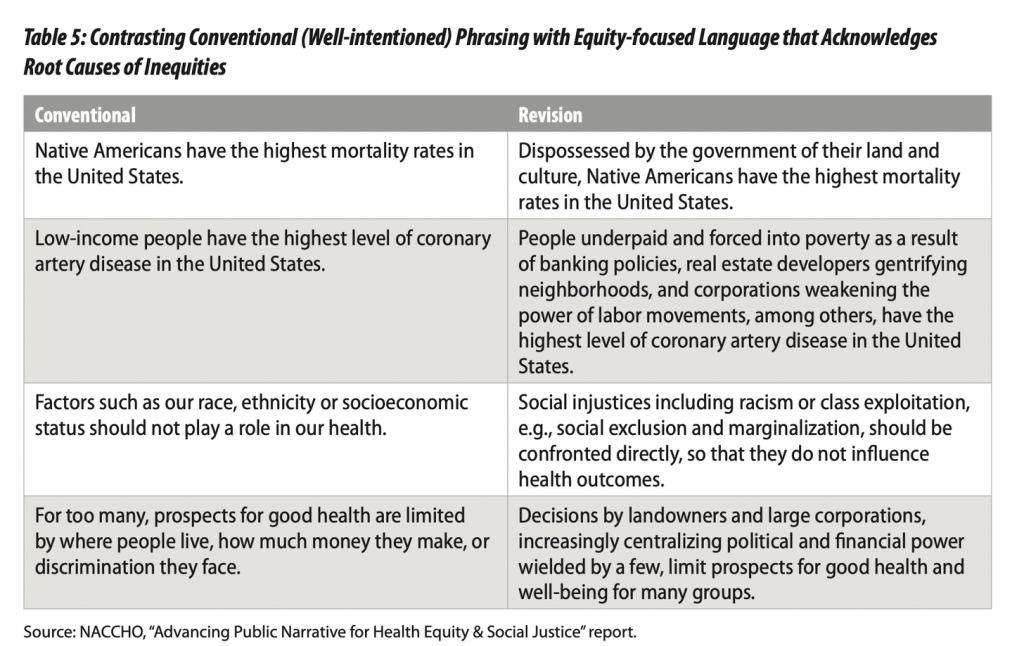

While I disagree that equality is political, I do understand that specific phrases come across as political. There’s no question that “Low-income people have the highest level of coronary artery disease in the United States” puts the focus on the level of CAD. But “People underpaid and forced into poverty as a result of banking policies, real estate developers gentrifying neighborhoods, and corporations weakening the power of labor movements, among others, have the highest level of coronary artery disease in the United States” starts a conversation about public policy.

Public policy discussions are immensely important. We need more of them in government, at the AMA, and in hospital board rooms. But as a content strategist, it’s important to know your audience. Do you know what audience doesn’t need a public policy discussion? A patient with CAD.

If it’s not usable content, who cares?

There’s a healthy tension between readability and accuracy. It’s our job as content strategists in healthcare to navigate that tension and find a middle ground. Even more challenging, there’s no one right answer. In the middle ground there will be disagreements. A good content strategy results in easier conversations, but copy and its constant updates will require constant conversations.

While obviously I feel the AMA and other public health groups could use more content strategy, I have a larger concern. The new guidelines are actively harming their ability to provide useful, actionable information. Perhaps with effort we can shift these guidelines. We need providers to use words that help reinforce equitable healthcare, but we also need them to use words that help their patients understand their health and take action.