In a recent UX Matters article by Peter Hornsby, Hornsby calls out Facebook for purposely designing an addictive application. He quotes Sean Parker, Facebook’s first president, on the company’s goal:

“How do we consume as much of your time and conscious attention as possible. And that means that we need to sort of give you a little dopamine hit every once in a while—because someone liked or commented on a photo or a post or whatever. And that’s going to get you to contribute more content. And that’s going to get you more likes and comments. It’s a social-validation feedback loop. … You’re exploiting a vulnerability in human psychology. The inventors / creators understood this consciously, and we did it anyway.”

[bolding added by me]

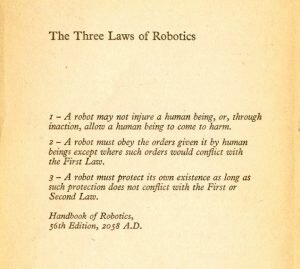

Hornsby was inspired by the realization that UX designers are essentially exploiting human vulnerability. So he created his own variation on Asimov’s 3 rules:

- A UX designer may not injure a user or, through inaction, allow a user to come to harm.

- A UX designer must meet the business requirements except where such requirements would conflict with the First Law.

- A UX designer must develop his or her own career as long as such development does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

But here’s my question: is Facebook, in Hornsby’s example, actually breaking any of these laws?

How Do You Define Harm?

I love Hornsby’s recommended rules. But the question I’m posing is how we define harm to our users. Is Facebook harming users by consuming as much of their time and attention as possible? Hornsby identified that his own goals were being undermined by his time on Facebook:

“Once we figure out what we want to do with our lives, we should take the time to reflect on how to achieve our goals, then get on with it. I have friends, a family, and work commitments. So, after some reflection, I ultimately decided that the time I was spending on Facebook was time that I would rather be spending elsewhere. Looking at the time I spent on Facebook objectively, it was probably not a huge amount of time. But subjectively, it felt like I was spending too much time and mental energy on something that wasn’t worth the price—particularly if I got drawn into an argument with strangers or possibly bots. Worse, the emotions I felt while I was engaged with Facebook bled into the rest of my day, affecting how I was feeling.”

Using myself as a counter-example, I check Facebook once or twice a day. I use it primarily to connect with friends and family in far off places. Since I’m terrible at returning phone calls (as are my cousins and siblings!) we comment on one another’s photos and posts to keep the conversation going. Facebook may undermine Hornsby’s goals, but it furthers mine.

That said, Hornsby’s certainly not alone in doubting the ethical nature of Facebook (and others). So I’m not trying to attack him personally. I just believe that calling Facebook’s goal unethical presumes an understanding or ownership of our users’ needs.

What is Our Responsibility?

I often see my role in UX as one of balancing the user’s need for freedom vs. safety. I’ve written before about how the need for a perception of control can be different from an actual need for control.

When I work on healthcare apps at Mad*Pow, we are often asked to help a user accomplish a long term goal by (essentially) tricking them into spending time on things they don’t care about.

For example, most people with rheumatoid arthritis want the pain to stop. Their doctors also want the pain to stop, as pain can be indicative of other issues. But the patient doesn’t want to go for walks or do hand exercises. Their reasons are sound in the short term. The exercises can be painful, and boring, and might take them away from the things they love, such as reading or spending time with family or simply not being in pain. We build apps that convince, trick, or motivate users (depending on how you look at it) to spend more time doing these exercises. Or we build them games that use the exercises. Or we get them moving in other ways.

Is this Manipulation?

You could say we’re exploiting vulnerabilities in human psychology. We work with behavior change researchers and run usability tests to understand how to get people to use an app more frequently and longer. We want them to use the app – and they usually don’t care if they do. But we tell ourselves we’re doing the right thing because it’s better for them in the long term. It will help them reach the long term goals they struggle to move towards.

If Facebook helps some people combat loneliness or connect with friends and family far away, is it ethical for Facebook to “trick” people into using the site more? If it makes other people feel more lonely or even harms their mental health, does that make it unethical?

I don’t think so.

Ethical Control vs. Choice

There’s no easy answer here. (Obviously. If there were, you’d know it, and wouldn’t be reading this.) We’re not overseers of the world, and it’s not for us to decide what’s right for each individual user. But there are things I believe we can, and should do, to take on some ethical responsibility. For example…

1. Don’t lie

You would think this one is obvious, so I’ll just leave it at that.

2. Learn about your users

Every user group is going to have different concerns and needs. You and your team may decide that your users need to be motivated or tricked into doing something good for them. You may determine that a seemingly innocuous headline (Lose Weight Today!) will trigger your audience (who needs to focus on healthy living, not fad diets). You will do a better job of helping people and making ethically sound choices if you gather details on behavioral demographics.

3. Pay attention to unintended consequences

If you design an app that you think will help people, and then it turns out it hurts them, consider how to make it better. One example I’ve heard of (though I can’t find the article now!) is an app that was intended to help people drink less by tracking their drinks. Frat houses turned the app into a drinking game. This brings up two questions for conscientious UX designers: Is the app still helpful to the target audience? and is there a way to amend the misuse of the app?

4. Learn and iterate

If your app is being misused, or causing harm, that does not make you a bad person. If your app is fantastic at attracting people, but makes their lives worse, that does not make you a bad person. If you learn all of this, rather than questioning your ethical soul, that’s an opportunity to improve the app! (Of course, if you do learn all of this and then determine it’s more important to have lots of users and less important to help them… well, I’ll judge you. But that’s your call.)

5. Ask questions

Ultimately, there will always be someone who disagrees with you. You might build Facebook to cure loneliness, and someone will think you’re being too lax and ignoring the harm it does. Or you might build an app that tricks people into exercising, and people will think you’re being too prescriptive and controlling. If you’re concerned with ethics in UX, the best thing you can do is ask questions – of yourself; of your users; of people who look, act, or think differently from you.

Acting ethically means acting according to “good values.” Values change from one person to the next. Where one person values quality of life, another values longevity. Where one person values time with friends above all else, another values privacy and security. The best thing you can do is keep caring, and keep considering.

Nir Eyal have extensively written about it, as an extension of his best seller “Hooked”. When I saw Peter’s article on UX Matters, I tweeted to Nir and he pointed me to https://www.nirandfar.com/2017/05/tech-companies-addicting-people-stop.html. Thin line, it is.

Thanks Vinish! I’ll check out Nir’s article now.